California Public Agencies Are Failing To Meet Their Annual Reporting Obligations Under Senate Bill 1029

California public agencies report on their capital expenditures in a variety of ways, including reports to their governing board and to oversight committees. These expenditures are subject to the agency’s annual audit and, in theory, compliant with administrative and accounting procedures. But, in truth, none of these approaches provides a complete understanding of what was built and how much was paid for it, undermining taxpayer efforts to assess the cost-benefit ratio of public capital improvement programs. In 2016, California passed Senate Bill 1029 requiring public agencies to provide an annual update on the debt they had issued. The intent was to create greater accountability. Unfortunately, public agencies are not complying and the ability of investors, policymakers, and taxpayers to monitor how public funds are being spent remains limited.

I left the California Debt and Investment Advisory Commission (CDIAC) in October 2019 after serving as its Executive Director for more than 9 years. But, my work to introduce best practices in debt administration and project compliance continues. I am committed to seeing that public agencies managing capital projects, whether financed by debt or not, do so in an efficient and responsible manner.

On February 12, 2015, California State Treasurer John Chiang convened a special task force to develop best practices guidelines on the fiduciary care and use of state and local bond proceeds. The Treasurer’s decision to form the Task Force on Bond Accountability resulted, in part, from the revelation that approximately $1.3 million was discovered missing during a routine audit of bond funds held by the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG), an issuer of bonds for local governments, nonprofit organizations, and private entities in the San Francisco region. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the bond money, which was earmarked for public parks and street improvements in downtown San Francisco, was allegedly embezzled by ABAG’s director of financial services.

The Task Force issued a final report on December 23, 2015, providing Guidelines for public agencies to ensure that bond funds were being used for only legal and intended purposes (https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cdiac/reports/task-force.pdf). One conclusion the Task Force drew from its work was that the absence of best practice guidelines represented a significant deficiency in the body of knowledge concerning the fiduciary care and use of state and local bond proceeds.

As the 2016 legislative session kicked off, Treasurer Chiang sponsored amendments to issuer reporting requirements administered by CDIAC. SB1029 (Hertzberg), was signed into law September 12, 2016, thereafter requiring issuers of public debt in California to submit an annual debt accountability report. Specifically, state and local agencies that submit a report of final sale to CDIAC after January 21, 2017 must also submit an annual report detailing the amount of principal outstanding, the amount of authority outstanding, and how and how much of the proceeds received were used.

Between April 4, 2016 and May 8, 2020, 9,656 issues of state and local bonds were subject to the reporting requirements of SB 1029. To my knowledge, this is the first assessment of how issuers are doing in meeting their obligation to submit the annual debt accountability report to CDIAC.

I randomly sorted the 9,656 issues to settle upon a sample size of 1,150 issues that would be significant at the 95 percent confidence level. These 1,150 issues accounted for $29.5 billion in bond principal sold.

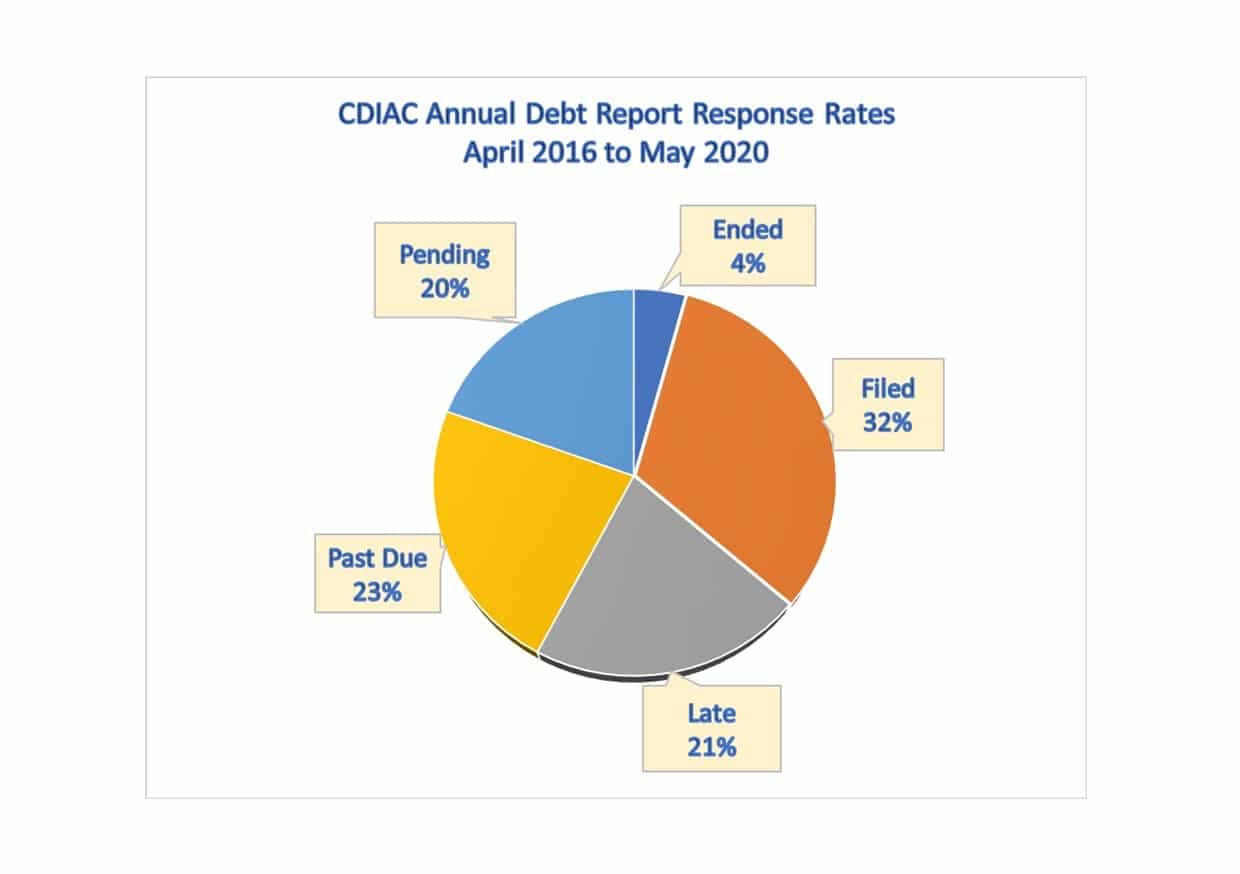

CDIAC assigns an issuer’s filing status to one of five buckets: 1) Ended because the debt has been paid off and proceeds spent; 2) Filed; 3) Late because the issuer missed the filing deadline; 4) Past Due because the issuer did not submit a report 12 months after it was due; and 5) Pending because the issuer has not submitted the report but the filing period has not closed.

Of the 1,150 random issues reviewed, the reporting obligation had ended for 45 (4%) of the issues. Three hundred thirty-six (29%) reports were filed on time. Two hundred twenty-five (20%) reports were late. Two hundred thirty-nine (21%) reports were past due and 205 (18%) reports were pending. As a caveat to these results, the COVID-19 crisis may be hampering issuer compliance reporting and CDIAC’s ability to post reports received.

In my next installment I will address who if filing, who is filing late, and who has not filed in compliance with SB 1029.

My purpose in writing this series is to instill in issuers an awareness of their responsibilities to investors, policymakers and, especially, to taxpayers. I continue to push for issuers to adopt better debt management and project tracking processes.

![Mark Campbell looks at how California debt Issuers are performing: A three-part series on LinkedIn [Part 1]](https://www.affiliatedmonitors.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/laptop-seth-schwiet-40984-unsplash_small.jpg)